Du Cane Court: a Build-to-Rent Masterpiece

Doing what we do, we become immersed in how innovative the Build-to-Rent sector is; how differently we do things and how we are changing the world of renting for good. We like to think of ourselves as ‘the future of renting’.

But there’s very little we are doing now that hasn’t been done before.

Last year, in the same vein, I wrote about Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. A 337 unit build-to-rent block built between1947 & 1952. This year, something a little different.

Ladies and gentlemen: I give you…. Du Cane Court, Balham. And the architect George Kay Green.

The Build-to-Rent Boom.

Whilst Le Corbusier’s apartment block ushered in Brutalist philosophy, George Kay Green’s came towards the end of a wonderfully varied period of Art Deco. Completed in 1937, some 15 years before the Unité d’Habitation, Kay Green was also responsible for Sloane Avenue Mansions and Nell Gwynn House.

During the time he was building these blocks for The Central London Property Trust, London was in the midst of a ‘between the wars’ BTR boom; 1300 blocks of 54,000 flats were built during this period. An incredible number, even by the ambitious standards of today. Probably the most well known of these is Dolphin Square, the ultimate 1930’s build-to-rent development of 1,250 flats, and associated ‘amenity’, retail parade and a swimming pool. By contrast, Du Cane Court consisted of between initially 632 apartments, and eventually 676. But they were all under one roof, which made it the largest scheme of its type.

Art Deco Build-to-Rent.

The questions that occupy us today; design, construction methodology, amenity provision, management, curation of service, were also uppermost in the mind of the 1930’s developer.

Whilst we may agonise over the advantages of modular construction or Off-Site Manufacturing (OSM) versus traditional build. Or high density, high rise blocks v low density low built schemes, back then they had similar concerns. Not quite the same concerns, but nevertheless, there were discussions over brick v steel frame or pre-stressed reinforced concrete. Or a combination, as was the case with Du Cane Court. At the time, it was considered to be very ‘avant-garde’. The windows and frames were similar to those designed by Mr Walter Crittall; steel frames dipped in molten zinc, but in the instance of Du Cane Court, they were supplied by W.H.Henley and Co.

In modern-day BTR, the size, shape and appropriateness of amenity is an on-going discussion. How far do we go to ensure a great living experience? What’s the balance between too much and too little; purposeful or pointless? Does amenity add to NOI or does it eat into it? Does it increase asset value or is it disregarded? Whatever the amenity philosophy was in the 1930’s, it’s clear that at Du Cane Court they were thinking along similar lines to modern day operators.

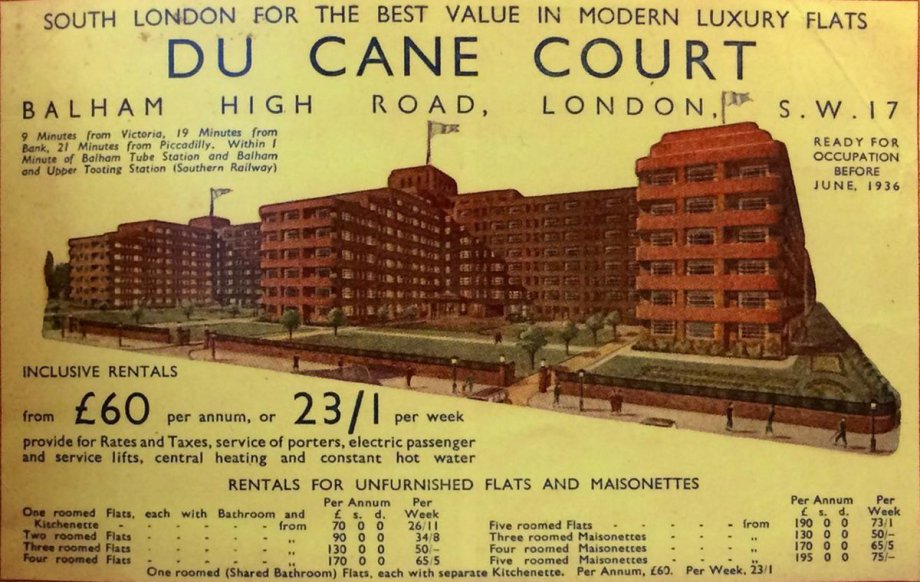

An advertisement for Du Cane Court from the 1930’s, and something of a teaser campaign proclaimed “South London for the Best Value in Modern Luxury Flats”. So, what could the eager residents expect for their (from) £60 per annum rent? (or 23s 1d per week if you’d rather).

There was amenity space aplenty; a seventh-floor restaurant, a ballroom, cards room and licenced bar. The original design provided for squash courts, playground and a crèche although they were never realised. The entrance was grand and spacious and, very much as today, was more like that of a 5* hotel than an apartment block. First impressions are crucial. Some things never change. Residents also had the option to hire a guest room for overnight stays and could call on a maid to help with cleaning, and provide general service when entertaining “at home”. The porter took in parcels and deliveries, dealt with minor requests and called taxis. Whilst the ‘back of house’ management looked after the residents and ensured the amenity space functioned smoothly. There was even an Express dairy to supply fresh milk and cream, butter and cheese.

As for technology, there was an ingenious gravity dependent, an internal postal system which allowed residents to post letters from their own floor from where they would slide into a glass-fronted post box. Telephone kiosks were placed on every floor and apartments were fitted with an electric clock and built-in radio which could receive two stations!

Each kitchen had a ‘hopper’ which would direct refuse directly to the basement, and the block had a central heating system that provided both hot water and heat which could be moderated by a thermostat in each flat. Each flat also had an electric fire.

All in all, it was comfortable convenient flexible living with great design, well-considered amenity and customer focussed service.

In fact, little of what we do now is new. If we look back we can see that what we now herald as ‘the future of renting’ has, in fact, been done before. Yes, our technology is light years ahead and taste in aesthetics has changed, but in essence, we’re not the trailblazers we thought we were. Similarities in ownership are also mirrored. The Royal Liver Friendly Society owned the freehold of Du Cane Court.

So, what happened to the 1930’s renting nirvana? Why did those 52,000 units built to usher in a new way of renting not survive? And could that happen today?

Well, the war happened. A mere two years after Du Cane Court was completed, in 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced that the deadline for German troops to leave Poland had expired and that subsequently Britain and France were at war with Germany. Hostilities escalated slowly at first, but as London became a prime target for the Luftwaffe, many people moved away from the capital. Rent controls were implemented and viable business dried up for the apartment blocks.

Like many, owners of Du Cane Court, The Central London Property Trust went bust and the blocks were broken up and sold off. Post-war, there was an even greater emphasis on ownership and a huge effort to provide social housing. Later, further rent regulation tinkering in 1965-74-77 & 80 discouraged large-scale PRS and, in fact, many institutional investors sold up and left the sector. So, Britain never returned to Build-to-Rent.

Until now.

(reprinted from my piece in Loft interiors "A BTR Tomorrow"